“Did the United States ever have a monarch?” asked one of the teenagers amassing outside the Vivian Beaumont before this week’s Wednesday matinee of The King and I. “Only a British one,” replied the teenager’s friend. “Our country was founded to get rid of all that.”

From that conversation, you might have thought that a student matinee of Hamilton not The King and I was about to begin. Having experienced the joy of watching high schoolers at both shows, I can only repeat what one of the kids said after King let out: “Why can’t history class be like this every day?”

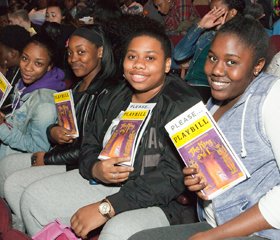

Sixteen talented teaching artists of LCT’s Education Department had prepared the approximately 910 students, from 11 New York City public high schools, with three workshops prior to the performance. The sessions explored a wealth of topics such as the geopolitics of 19th-century Asia, the idea of a “dominant culture” as reflected in the show’s song “Western People Funny,” and the 19th-century novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. A follow-up workshop explored such topics as the relationship between Anna and the King and the challenge of casting these roles.

After the matinee, the students had a chance to ask questions of several cast members, who, shed of their silk costumes and attired in civvies, were almost unrecognizable. The performers were clearly energized by the students’ response during the performance, which was – no surprise! – especially animated during the forbidden-love scenes between Tuptim and Lun Tha.

One student wondered what it was like for the actresses to play women characters who seemed to lack power. Ruthie Ann Miles, who portrays Lady Thiang, acknowledged that the characters could appear subservient. She added, however, “These women are not stupid…I think [they] are the smartest people in the play.”

Facing a similar student question, Ashley Park, who is Tuptim, replied, “A central struggle of the show is what happens when a woman of modern ideas” – Anna Leonowens – “is brought into a community that is so traditional.”

Another student asked Anna’s interpreter, Kelli O’Hara, whether Anna’s calling the King a “barbarian” constituted treason? O’Hara replied that Anna works throughout “the whole show to help him move past any charge of barbarism.” She added: “I’m trying to get him to stop whipping women like Tuptim.” And, she stressed, the real-life king on whom the character is based “allowed change.”

Another student asked about Tuptim’s alterations to the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the “Small House” ballet she presents to the King. Park replied, “She interprets the story so that she personally can relate to it.”

At these talkbacks, students are always interested in the youngest characters. A talkback questioner wondered what the character of Louis – Anna’s 12-year-old son – might have done later in life. O’Hara replied that his mother, after 5 years in Siam, had taken Louis back to England. Eventually, he returned to Siam, resumed his close relationship with his childhood friend, King Chulalongkorn, and married a half-Siamese woman. “He had been so affected by his childhood years with Siamese people,” O’Hara said, “and in a way he wanted to be one of them.”

Brendan Lemon is the American theater critic for the Financial Times and the editor of lemonwade.com.