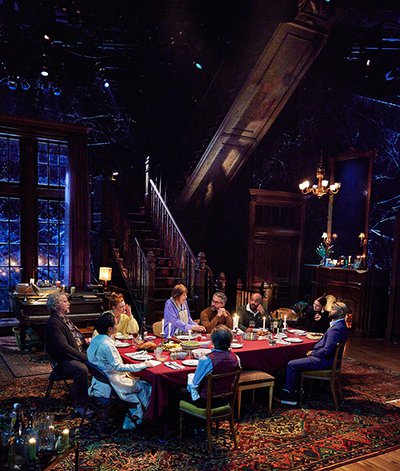

Volumes would be needed to document the career of the set designer John Lee Beatty: for Lincoln Center Theater alone he has worked on two dozen productions. In my recent conversation with him I therefore decided to focus on Epiphany, the play by Brian Watkins and directed by Tyne Rafaeli now in the Mitzi E. Newhouse space, and, more specifically, on the most salient feature of Beatty’s set: a majestic, two-story staircase.

So monumental was the construction of the staircase, Beatty said, “that we had to raise the entire floor of the theater by three feet.” That feat was accomplished only after Beatty had come up with an overall set design acceptable not only to himself but to Rafaeli. “I have stacks and stacks of tries to get the design right on this production,” Beatty said. “I placed staircases all over the place. The winner is huge and very noticeable. When I showed it to Tyne she smiled and gave her agreement.”

One of the unusual features of the staircase is that we see the part stretching from the second floor to the third. “We don’t usually glimpse the underside of a staircase,” Beatty said. “In this case, it’s beautifully built, of wood, with hidden metal supports.”

As for the lower part of the structure – the stairs stretching from a landing down to the first-floor playing area – Beatty commented, “In this play, they’re not quite Hello, Dolly! theatrical, but each time that the Marylouise Burke character” (she’s Morkan, the owner of the old house), “descends your focus is riveted to her. The character is older so part of us watches her while praying that she doesn’t take a tumble.”

As a child, Beatty took a tumble or two on the staircase in the old house where he grew up, in southern California. “At bedtime, my parents would say, ‘It’s time to climb the wooden hill.’ Once I was tucked in, there was a clear divide between my child’s world, upstairs, and the adults’ world, downstairs.” Beatty’s parents were academics – his father was dean of students at Pomona College – and once Beatty was upstairs his parents would resume their professions. “One of the memorable sounds of my childhood was my parents typing away. To this day, I find the clacking of a typewriter soothing.”

That a staircase is both the division and the connection between worlds applies not only to Beatty’s childhood but to the universe of Epiphany. “As the play goes on,” he said, “there’s a growing sense that the upstairs represents heaven or at least somewhere metaphysical and that downstairs is the earthly realm.” He added: “The other large element of the set, a rear window, contains religious symbolism. Embedded in it is a 14-foot cross shape.”

Late in the play, with that cross as a backdrop, one of the characters sings, hauntingly, an Irish folk song. “That area of the Mitzi,” Beatty said, “is a favorite of Patti LuPone. She thinks there’s something magical there.”

If certain places in the space remain unvarying in their associations, Epiphany’s theater itself to Beatty is mutable. “You never quite know what you’ll be seeing when you walk in there to watch something.” Referring to a 1992 play by Wendy Wasserstein, for which he designed the sets, Beatty added, “When I look at Epiphany I can’t believe that this is the same place where we did The Sisters Rosensweig. The Mitzi is the great chameleon.”

Brendan Lemon is the editor of lemonwade.com